On Markdown

In the beginning, there was LaTeX

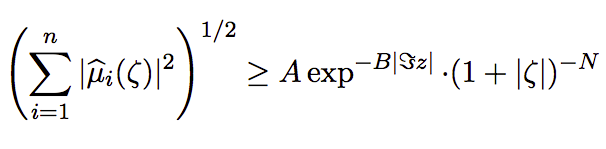

As a former mathematics student, I have an unusual soft spot for LaTeX. Despite it's obscenely verbose and quirky syntax, it was more than a breath of fresh air compared to Word's Equation Editor. (It required a highlighting, 4 clicks, and keyboard input to create an exponent, if I remember correctly.) But not only does LaTeX keep your fingers on the keyboard, it's output is the most beautiful thing I've ever laid eyes on. I mean, just look at this inequality:

Even using a slew of macros and shortcuts, reading LaTeX code is burdensome at best, and this will forever keep it's use out of the main stream. Worse, making formatting changes in LaTeX is onerous. Luckily for math students their are really great one's already created that are perfect for your homework, and journals traditionally provide their own. (My University library did not, however. Spent at least 8 hours and an argument with the librarian working on the Title page with spots for my advisors' signatures'.) Because of this, LaTeX will never be a mainstream word processor.

However, I think there is one core design aspect of LaTeX that is far more ideal than traditional word processors: separation of corpus and design.

Enter Markdown

Markdown was created in 2004 with the idea to "make writing simple web pages, and especially weblog entries, as easy as writing an email" (quote from the late Aaron Swartz's blog post announcing the release.) It has gained a deal of popularity in web culture on sites such as reddit and GitHub, as well with some excellent hacker tools like iPython Notebook and Octopress***. (This site is powered by Octopress and each post is written in Markdown.)

There is a more thorough example on wikipedia Wikipedia, but for example *italics* renders as italicts, **bold** as bold, and [links](http://skien.cc) as links.

The really clever thing here is that for most documents, there is very limited formatting to add. For web documents, like blog posts and comment sections, you mostly need sections, paragraphs, italics, bold, links, inline images, and inline quotes. Developers like the ability to add in text code and

inline code blocks.

Best of all, you don't have to write in HTML (Who want's to write an article in raw HTML? Ain't nobody got time for that.) and you can achieve a great deal of formatting.

A Business Case

The key is separating the writing of a document from the design of a document, and Markdown achieves this with flying colors. For the author, the marked up text is easy to read and easy to write. For the designer, the CSS likely already exists if you have a website (although they may wish to update it slightly.)

A system for sharing these documents like developers share Gists could easily replace email attachments and grant extra security (either through obscurity or something stronger.) Authors could also update or take down old documents, whereas an attachment lives on in the receivers inbox forever. (Nothing would would prevent the viewer from saving the content when they see it, but this would require premeditation and would be a rather uncommon event in my opinion.)

If you'd like to create PDF's, it's not too painful create a base template in, you guessed it, LaTeX, and then produce PDF's for printed material (or for when you'd really like to send an attachment rather than a link.) And if you really need to, you can even generate a Word document. After the initial fixed cost of developing these templates, you'll have a dead simple way to generate standardized documents without the variable cost of worrying about format on each one.

Many free tools exists to work with Markdown as well. One of my favorites is Mou, which allows you to view a rendered version of the file side by side with an editor. (I'm using it now.) Dillinger does the same thing in the browser, and can connect to Dropbox, GitHub, and Google Drive. As more tools like these emerge, I predict a sharp decline in demand for over powered text editors like Microsoft Word.